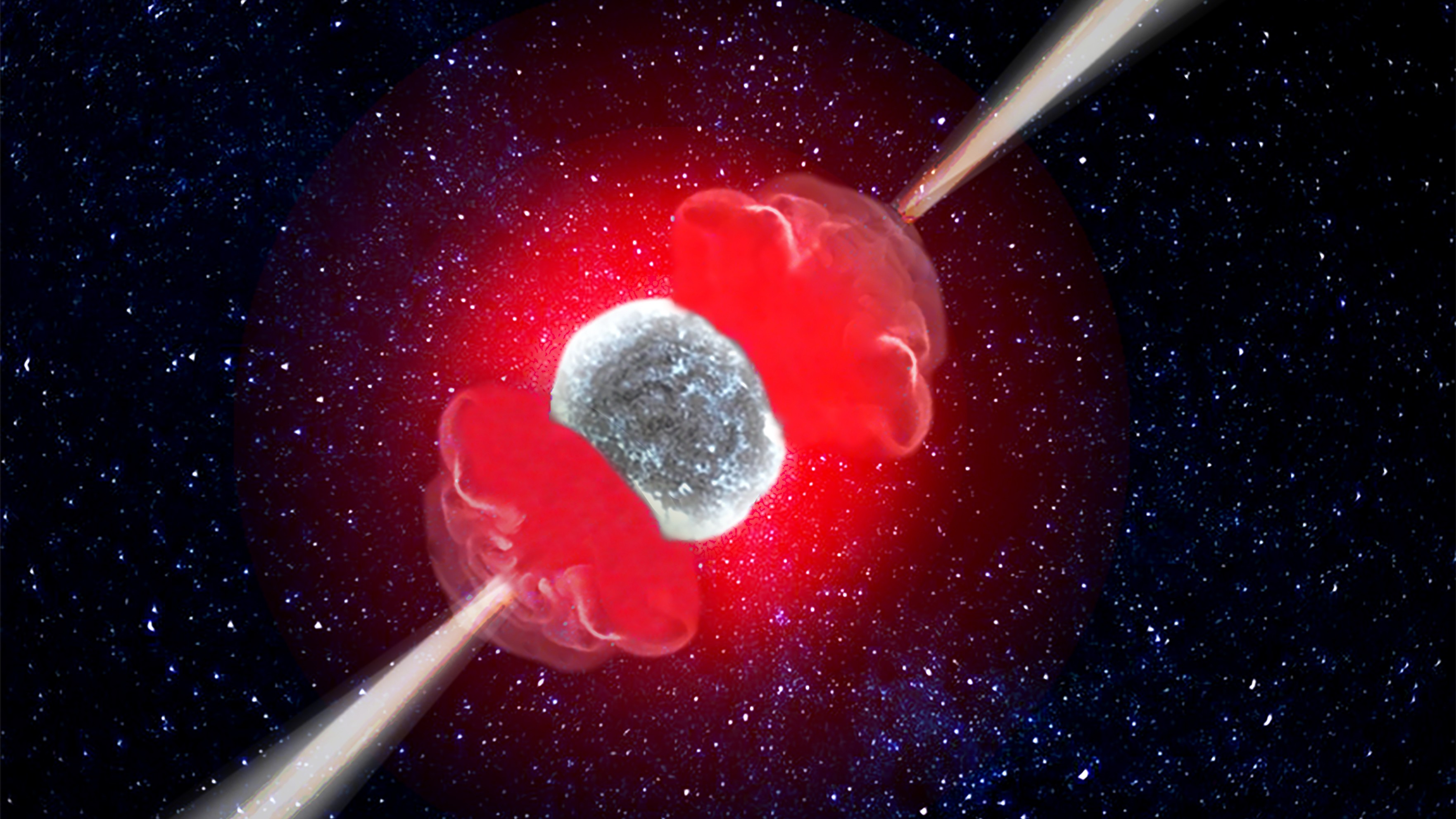

An international team of scientists, including astronomers from the Universities of Bath, Leicester and Warwick, have found evidence for the existence of a 'hot cocoon' of material enveloping a relativistic jet escaping a dying star. The research is published in Nature.

A relativistic jet is a very powerful phenomena which involves plasma jets shooting out of black holes at close to the speed of light, and they can extend across millions of light years.

Observations of supernova SN2017iuk taken shortly after its onset showed it expanding rapidly, at one third of the speed of light, making it the fastest supernova expansion measured to date. Monitoring the outflow over many weeks revealed a clear difference between the initial chemical composition and that at later times.

Taken together, these are indicators of the presence of the much theorised ‘hot cocoon’, filling a gap in our knowledge of how a jet of material escaping a star interacts with the stellar envelope around it and providing a potential link between two previously distinct classes of supernovae.

The supernova signals the final moments of a massive star, in which the stellar core collapses and the outer layers are violently blown off. SN2017iuk belongs to a class of extreme supernovae, sometimes called hypernovae or GRB-SNe, that accompany a yet more dramatic event known as a gamma-ray burst (GRB).

These bursts are highly relativistic, narrow beams of material ejected from the poles of the star which glow brightly first in gamma radiation and then across the entire electromagnetic spectrum.

Until now, astronomers have been unable to study the earliest moments in the development of a supernova of this kind, but luckily SN2017iuk was close-by in astrophysical terms– at roughly 500 million light years from Earth – and the GRB light was comparatively dim, allowing the supernova itself to be detectable early on.

Dr Patricia Schady, from the University of Bath’s Astrophysics Group, was part of the team of researchers around the world who used a variety of telescopes on Earth and in space to examine the supernova in detail across wavelengths of light.

She said: “We detected the GRB-SN at the very earliest stages of its evolution, and this triggered an intensive follow-up campaign. “It became very quickly apparent that the light curve of this event was not evolving as your standard GRB, and the first spectra revealed a supernova that was not like any other GRB-SNe that we had seen before.

“My role was to use an instrument called the Gamma-ray Burst Optical/Near-infrared Detector, or GROND, to analyse the gamma-ray burst element of this event. GROND, which was built at the Max Planck Institute, allows us to analyse bursts in multiple colours simultaneously, which allows the evolution of the supernova thermal emission to be monitored as it cools.”

Dr Rhaana Starling, Associate Professor in the University of Leicester’s Department of Physics and Astronomy said: “When the first sets of data came in there was an unusual component to the light that looked very blue, prompting a monitoring campaign to see if we could determine its origin by following the evolution and taking detailed spectra.

“The gamma-ray burst itself looked quite weak, so we could see other processes that were going on around the newly-formed jet which are normally drowned out. The idea of a cocoon of thermalised gas created by the relativistic jet as it drills out of the star had been proposed and implied in other cases, but here was the evidence that we needed to pin down the existence of such a structure.”

A coordinated approach using a suite of space- and ground-based observatories was required to monitor the supernova over 30 days and at many wavelengths. The event was first detected using NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory.

Data obtained with the Gravitational-wave Optical Transient Observatory (GOTO) helped to track the supernova light, while spectroscopy was obtained through dedicated observing programmes including initiatives by the STARGATE Collaboration headed up by Professor Nial Tanvir at the University of Leicester, which uses 8-m telescopes at the European Southern Observatory.

Professor Tanvir, Lecturer in Physics and Astronomy at the University of Leicester said: “The relativistic jet punches out through the star as if it was a bullet being fired out from the inside of an apple. What we've seen for the first time is all the debris that explodes out after the bullet.”

Speeds of up to 115,000 kilometres per second were measured for the expanding supernova for approximately one hour after its onset. A different chemical composition was found for the early expanding supernova when compared with the more iron-rich later ejecta. The team concluded that just hours after the onset the ejecta is coming from the interior, from a hot cocoon created by the jet.

Existing supernova production models proved insufficient to account for the large amount of high velocity material measured. The team developed new models which incorporated the cocoon component and found these were an excellent match.

SN2017iuk also provides a long-sought link between the supernova that accompany GRBs, and those that do not: in lone supernovae, high speed outflows have also been seen, with velocities reaching 50,000 kilometres per second, which can originate in the same cocoon scenario but escape of the relativistic GRB jet is somehow thwarted.

Core-collapse supernovae without GRBs are usually found much later after their onset, giving scientists very little chance of detecting any signatures of a hot cocoon, whilst cocoon features in GRB-associated supernovae are usually hidden by the bright, relativistic jet.

The rare case of SN2017iuk has opened a window onto the earliest stages of this type of supernova phenomenon, allowing the elusive cocoon structure to be observed.

This research was led by the Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía and was funded by the Science and Technologies Facilities Council (STFC) European Research Council (ERC) and UK Space Agency (UKSA).