There have been five mass extinction events in the Earth’s history, including climate change caused by volcanoes and an asteroid hit that wiped out the dinosaurs.

In general, geographically widespread animals are less likely to become extinct than animals with smaller geographic ranges, offering insurance against regional environmental catastrophes.

However, a study published in Nature Communications has found this insurance is rendered useless during global mass extinction events, and that widely distributed animals are just as likely to suffer extinction as those that are less widespread.

Large numbers not insurance against extinction

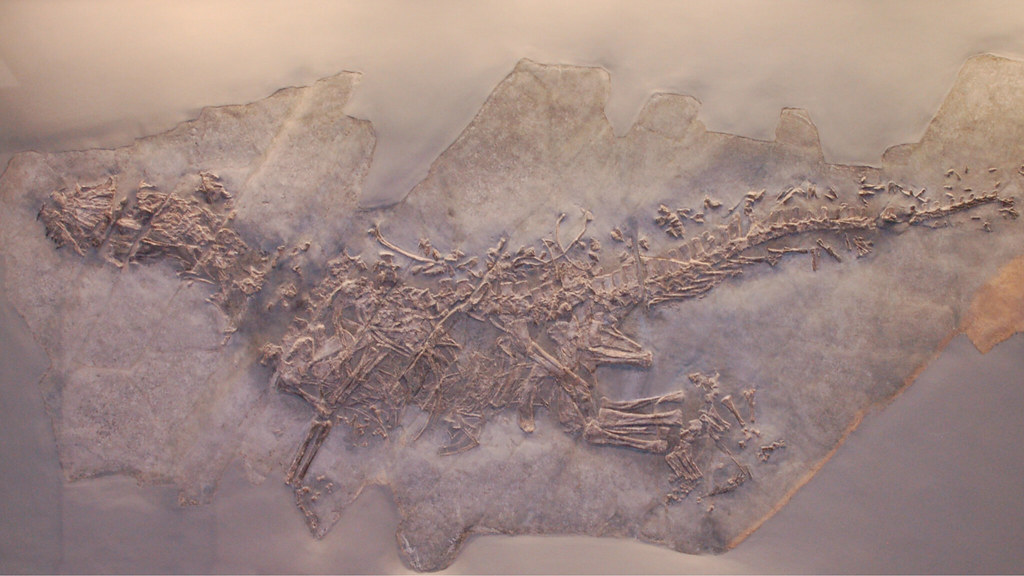

The research by Dr Alex Dunhill at the University of Leeds and Professor Matthew Wills from the University of Bath’s Milner Centre for Evolution, explored the fossil record of terrestrial (land-living) vertebrates (including dinosaurs) from the Triassic and Jurassic periods (252-145 million years ago).

They found that although large geographic ranges do offer insurance against extinction, this insurance disappeared across a mass extinction event that occurred around 200 million years ago (at the Triassic-Jurassic boundary) associated with massive volcanic eruptions and rapid climate change which caused the demise of around 80 per cent of species on the planet.

During this catastrophic event many groups of crocodile ancestors became extinct, which paved the way for the dinosaurs to rise to dominance in the subsequent Jurassic Period.

Dunhill and Wills mapped how the geographical distribution of groups of organisms changed through the Triassic-Jurassic periods. These distribution maps were then compared with changes in biodiversity to reveal the relationship between geographic range and extinction risk.

This is the first study to analyse the relationship between geographic range and extinction in the terrestrial fossil record and the results are similar to those obtained from the marine invertebrate fossil record.

Alex Dunhill, who started the work at Bath and is now at the University of Leeds, said: “The fact that the insurance against extinction given by a wide geographic distribution disappears at a known mass extinction event is an important result.

“Many groups of crocodile-like animals become extinct after the mass extinction event extinct at the end of the Triassic era, despite being really diverse and widespread beforehand.

“In contrast, the dinosaurs which were comparatively rare and not as widespread pass through the extinction event and go on to dominate terrestrial ecosystems for the next 150 million years.”

Mass extinctions "shake up the status quo"

Co-author Matthew Wills from the University of Bath’s Milner Centre for Evolution commented: “Although we tend to think of mass extinctions as entirely destructive events, they often shake up the status quo, and allow groups that were previously side-lined to become dominant.

“Something similar happened much later with the extinction of the dinosaurs making way for mammals and ultimately ourselves.

“However, our study shows that the ‘rules’ of survival at times of mass extinctions are very different from those at ‘normal’ times: nothing is ever really safe!”

Dr Dunhill added: “These results shed light on the likely outcome of the current biodiversity crisis caused by human activity. It appears a human-driven sixth mass extinction will affect all organisms, not just currently endangered and geographically restricted species.”

The University of Bath’s Milner Centre for Evolution is the first dedicated Centre for research and public engagement for evolutionary science in the UK. It is named after alumnus Dr Jonathan Milner who donated £5 million in June towards establishing the Centre.

An impressive 85 per cent of the University of Bath’s Biological Sciences research was judged as world-leading or internationally excellent in the recent independently-assessed Research Excellence Framework 2014.