Half of all burn injuries are suffered by children, and most of these are due to scalds from hot drinks or bath water.

Around 5,000 children a year are treated in hospital for burns in England and Wales. In the last year, the South West UK Children’s Burn Centre at Frenchay Hospital in Bristol has treated more than 800 children for serious burn injuries.

When a child with a small burn develops a high temperature, there’s no easy way of knowing if they have a serious bacterial infection, or simply a cough or cold.

Even a very small burn can quickly become infected and cause serious illness.

Around 10% of children who suffer burns become infected by disease-causing bacteria – which can increase the likelihood of scarring, longer hospital stays and even sudden death.

Treatment can be slow, painful and ineffective

The way clinicians currently treat infections resulting from burns can cause three distinct problems:

- if the treatment team suspect an infection beneath a burn dressing they usually remove it – increasing the patient’s pain and the probability of scarring, as well as financial costs

- ineffective antibiotics – they are usually used to treat infection, but in recent years there have been an increasing number of cases where they’ve proved ineffective due to bacterial resistance. In some cases no antibiotics will be effective in treatment

- fast diagnosis – tests can take up to a couple of days, but children are particularly at risk from the effects of infection, due to their relatively poor immunity. They can quickly develop a condition called toxic shock syndrome, which if left untreated can be fatal.

Bacteria-killing viruses and fluorescent dye

To overcome these potential pitfalls with existing infection treatment, scientists at the University of Bath are looking at making advanced burns dressings which monitor the burn environment and treat infection.

They are doing this by covering the wound dressing in nanocapsules which would burst open when a disease-causing bacteria was detected and release:

- acteriophage viruses which kill bacteria

- a fluorescent dye, alerting clinicians to an infection more quickly.

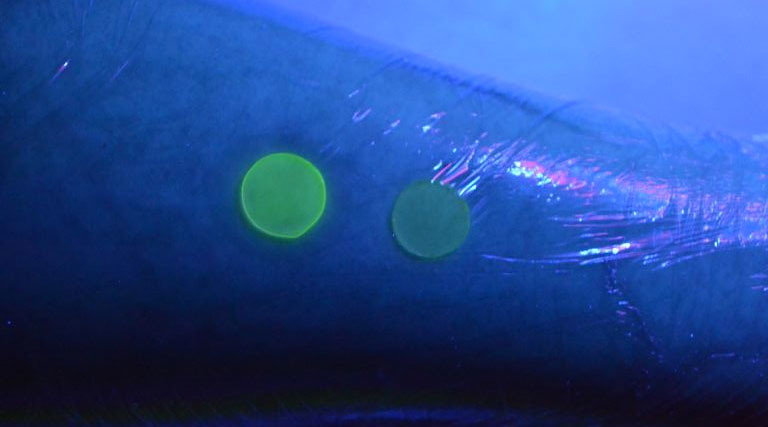

The technology is based on two concepts - that it only reacts in the presence of life-threatening bacteria, and that the florescent dye only shows up once the nanocapsules have burst.

Using a UV light, doctors can quickly check whether there is infection by seeing if the dressing glows. The nanocapsules are activated when they come into contact with toxins produced by harmful bacteria, so do not release the dye in response to normal bacteria that live on the skin.

A clinical research team has been assembled at Frenchay Hospital to collaborate with the University of Bath team to help produce dressing prototypes and, ultimately, conduct randomised, controlled clinical trials in hospitals.

There is also close collaboration with industry partners, including Mölnlycke Healthcare, who develop appropriate dressings.

Responsive, antimicrobial dressings could revolutionise the diagnosis and treatment of scalds in thousands of children in the UK annually and, ultimately, millions worldwide.

So far, the dressing has been tested on skin samples in the laboratory, but trials in humans are still some years away.

Gel formula offers additional treatment

As part of a related project, researchers at University of Bath are developing large-scale methods of producing the nanocapsules, and incorporating them into a gel formulation for topical application to the skin.

Different burns require different approaches to treatment, so developing a gel for topical skin application in addition to the wound dressing would allow this unique technology to be applied under a wider range of circumstances.

REF submission

This research was part of our REF 2014 submission for Chemistry.