The human body is home to trillions of bacteria, most of which are entirely harmless to us. Some, however, can lead to infections. Unlike its sore-throat-causing cousin, Streptococcus agalactiae, Group B Streptococcus (GBS) is commonly found in the lower intestines, and in women, can be found in the vagina. During childbirth, however, the bacteria can transfer to the newborn baby. In newborns, the bacteria can cause serious health conditions, such as sepsis; a life-threatening situation where the body over responds to an infection and begins to cause severe damage to itself.

For newborns in the UK, the threat from GBS is low. With access to doctors and emergency care, infections can be treated rapidly.

However, this is not always the case in low and middle-income countries. For many, childbirth may occur at home, and access to healthcare such as doctors or a hospital may be limited. In these situations, GBS can develop into a real and dangerous risk, with an estimated 147,000 infants dying as a result.

Emelie Alsheim, a PhD student in Professor Toby Jenkins' research group in the Department of Chemistry, has been developing a rapid, accurate and easy-to-use test for GBS, requiring only a lower vaginal swab sample.

Current testing for GBS

Tests for Group B Streptococcus do exist, but they have their problems. Current tests use a ‘culture dependent’ method. This means swabs are cultured in a specialised broth, and then plated on solid agar, to identify GBS colonies. As cultures need to grow for 24-48 hours before they can be identified, the correct treatment may be delayed by several days. There are alternatives that can give quicker test results, but these are more expensive to carry out. Another disadvantage of these tests is the need for specialised equipment and trained staff, which further hampers their effectiveness in low and middle-income countries.

GBS is known as a ‘transient’ bacterium that comes and goes in the body. This means that while it can be tested for earlier in pregnancy, it may only be present in the vagina temporarily. If someone has tested positive for GBS early in the third trimester, by the time they go into labour, this result may no longer be true. The opposite is also true; you may test negative for GBS late in pregnancy, but the bacteria may be present by labour, risking transmission to the newborn.

This inconsistency can lead to stress and anxiety in mothers, and the prescription of unnecessary antibiotics. If the test gives a false negative, there’s a risk of potential transmission to the newborn. Rapid bedside testing for the presence of the bacteria during labour would be revolutionary in the fight against GBS.

Developing a quicker, cheaper, and accurate test

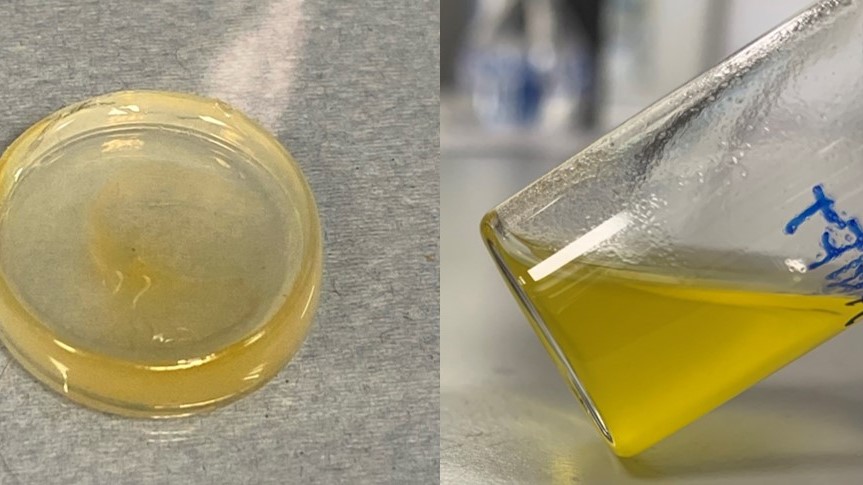

In developing a quick and cheap test, Emelie made use of a phospholipid vesicle system, similar to that used by Toby Jenkins’ group to detect bacteria in burn wounds. Phospholipids are fatlike substances made from molecules with a hydrophilic head and a hydrophobic tail. So that the tails don’t touch water, they join up with other tails, forming two layers of phospholipids. The two layers then join to create a sphere, called a vesicle, with a pocket inside that can be filled. In Emelie’s study, she filled the vesicle with a fluorescent dye, carboxyfluorescein which was quantified using a fluorimeter.

Vesicles mimic the appearance of human cells, which GBS will try to attack. As GBS attack the vesicle and tear apart the phospholipid layers, the fluorescent orange dye leaks out and changes colour, turning green in the presence of GBS. This allows for the result to be rapidly confirmed without specialised equipment or computers.

Once Emelie had validated the test’s ability in a laboratory setting to detect GBS, she compared it to the other available test methods by using donated lower vaginal swabs from non-pregnant women. She looked at three key properties of the test; the specificity, sensitivity, and accuracy.

Specificity looks at how many of the negative samples are truly negative. Sensitivity looks at how many of the positive samples are truly positive. Finally, the accuracy looks at how likely the test is to give a valid result. For each of these properties, Emelie found her new testing method scored on average 83% across all three characteristics compared to the results of the gold standard culture-based method.

Emelie was also keen to ensure the new test could be carried out at bedside during labour. This would allow the rapid detection of bacteria and for treatment to be sought almost immediately if necessary. Compared to other methods, this new test requires only 45 minutes to return a result. While there are other methods that can match this quick turnaround, they are expensive and need specialised equipment and training. Emelie’s new test can be carried out by an untrained specialist, in a similar way to the lateral flow COVID tests, allowing for unprecedented bedside testing.

Taking the next steps

While the early results of this new testing method are positive, it’s still in the early stages of development. Emelie and the researchers in Toby Jenkins’ lab have highlighted more testing is needed around using swabs to collect samples. They have also suggested the next steps are to trial the testing kit in pregnant women.

The development of this accessible and efficient test is a strong step forward in combating infant mortalities due to GBS.

Crucially, it will also give mothers the peace of mind and the confidence to seek out further medical help if needed, allowing for the correct treatment of GBS to be given as soon as possible.