For the past 12 months, University of Bath political, security and defence experts Dr Patrick Bury, Dr Stephen Hall and Professor David Galbreath have been following developments in Ukraine and Russia closely, providing their reflections and analysis for UK and international media on a daily basis.

As the first anniversary of war in Ukraine is marked on Friday 24 February 2023, we get their expert take on what’s happening on the front-line in Ukraine, the political and economic ramifications in Kyiv and Moscow, as well as how the wider world has responded in terms of aid and support.

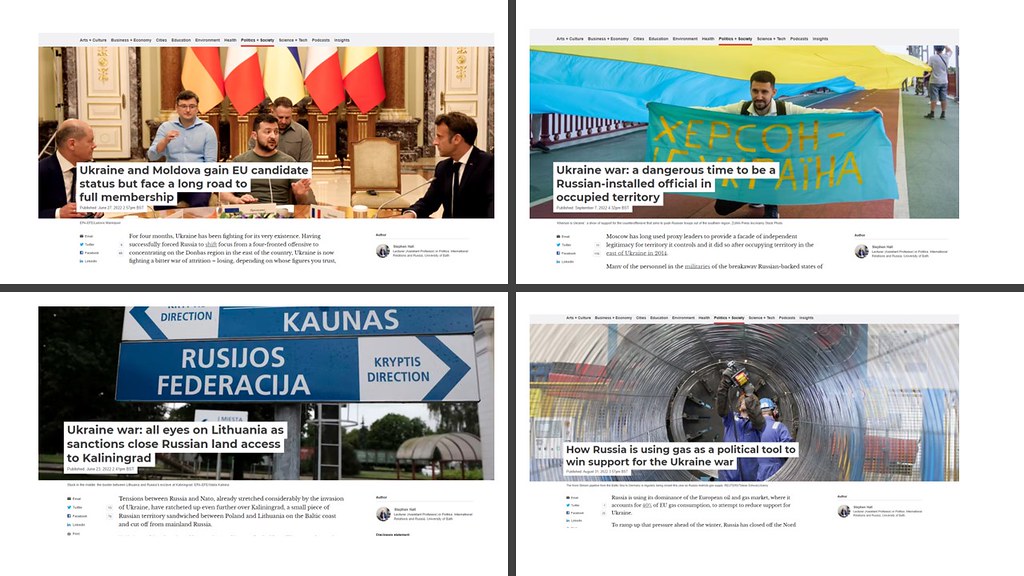

In the sections below you'll also find recent examples of interviews and comment provided by our academics on this topic across TV, radio and print from recent months.

Life on the battlefield: Dr Patrick Bury

What’s the last year of war taught us? There are many things, but to my mind probably the most important is that despite all the new – and old – technologies used so far in this war, the will to fight and cohesion is paramount. The Ukrainian will to defend their homeland against an invading Russian onslaught proved decisive in the early stages of the war, buying time for western support and the expansion of their military forces.

Strategically, while Russia opted for an ill-conceived coup de main to decapitate the Kyiv government, Ukraine prudently recognised that it could afford to trade space for time, ceding ground and allowing Russian formations to pass by before targeting their logistics. This forced the end of the first stage of the war in April.

After its withdrawal from around Kyiv, Russia revised its aims downward and adopted a strategy better suited to its forces’ strengths – an intensive artillery-heavy campaign of attrition focused on the Donbas. By the summer this was indeed proving very effective, but the introduction of western HIMARS turned the tide by allowing Ukraine to hit Russian ammo dumps and thereby forcing them to reduce their rate of fire. Meanwhile, the Kharkiv offensive showed that, backed by US intelligence, the Ukrainians were more than capable of conducting their own offensives, as did the less stunning Kherson campaign in September.

The latest stage of the war has seen Russia double-down on its war of attrition in the Donbas, but compensating for its losses in armour and lower rates of artillery fire with often freshly mobilised and undertrained infantry. Facing experienced and well-trained Ukrainian forces, they have again taken some of the heaviest casualties of the war.

~

For the Ukrainians manning snowy trenches and rubbleised buildings around Bakhmut its all about holding on and inflicting heavy casualties the waves of attacking Russian infantry. So far, although they have had to cede some ground, they are still holding on here, and in other important places in the east, like Kreminna.

The big question that everyone is trying to understand is if the recent attacks ordered by new commander General Gerasimov mark the start of the expected Russian spring offensive, or do they have more forces up their sleeve for later?

At the moment, it’s difficult to call exactly, but my hunch is its probably the former – the Russians have taken so many losses that they would probably need another round of mobilisations to generate the forces needed for a major offensive – but we’ll know in the coming weeks. For the Ukrainians, the operational plan is all about holding the line whilst committing as few of their reserves to the defence as possible. They’ll need them largely intact to launch their own combined arms offensives in the summer with Western tanks to take back lost territory. If they can protect, sustain and use these forces correctly they have a decent chance of punching through Russian lines, perhaps in the east around Kreminna-Svatove, or towards Melitopol. Another option would be Crimea, but it carries escalatory risks. A one-two punch towards Kreminna, followed toward Melitopol would make a lot of sense. But the Ukrainians are great at surprises so let’s see.

With both sides still unwilling to negotiate, it looks like there is at least another 6 to 8 months of heavy fighting ahead. There might well be a window of opportunity for negotiations after the summer, but both sides have to want them. Moreover, we are not out of the nuclear woods yet, and if Putin is facing major defeat I would expect him to escalate up the nuclear ladder to try to freeze the conflict.

~

Patrick’s research focuses on warfare and counterterrorism. As a former British Army infantry Captain and NATO analyst he has over two decades’ experience working in the security sector as a practitioner, analyst and academic. He is also a UK Future Leaders Fellow. Since the start of the conflict in Ukraine, analysis and comments from Patrick has featured in thousands of media packages, including for AlJazeera, RTE and BBC.

From Moscow and Kyiv: Dr Stephen Hall

The Russian reaction to the war has been muted at both public and elite levels. While there have been few protests, conscription offices have gone up in flames. While public opinion polls claim that most Russians support the war, they don’t show the high refusal rate, or acknowledge that Russians know which answer to give.

The regime relied on fostering public apathy and it is now difficult to mobilise support, witnessed by at least 400,000 Russians fleeing since the war began, amid growing unease that the Russian public must do more than support the regime from the comfort of the sofa. Yet, it will take a lot more for mass protests to occur. There are reports that most Russian elites secretly dislike and resent the invasion. However, this does not mean that Putin will be removed in an elite coup soon. None of the elite will raise their heads above the parapet before someone else does and Putin – like many autocrats – is adept at playing elite groups against one another. In a personalist system like Russia, elites are too focused on trying to please the boss, but because the invasion was a closely guarded secret few know how to properly react and are flailing to find a response.

The economic situation is likely to continue to deteriorate. While regime modernisers have worked hard steering the economy through sanctions, the Russian economy will suffer. Sanctions are a blunt tool, which only the West has implemented. However, Russia’s economy was pointed towards Europe, and it will take time to re-calibrate it towards Asia. Russia is selling oil and gas to new partners but at significant discounts, so resource revenues are lower, and an overdependence on China is likely. Most technology used in everyday products came from the West and import substitution will only paint over the cracks. Stagnation in Russia remains a real possibility.

Ukraine is also hurting economically having been decimated by war and reliant on Western military and financial aid. However, Ukraine has one thing Russia lacks, which is spirit, epitomised by the two leaders. Putin is ensconced in the Kremlin or a bunker and has yet to go to the front line. By contrast, Zelensky has toured the battlefields, made nightly speeches to Ukrainians and consistently shored-up support for Ukraine in the West. The contrast is pronounced, and Zelensky has shown himself a real leader and hero.

~

Stephen’s research focuses on post-Soviet politics, in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus, and authoritarianism. His upcoming book will address the issue of authoritarian learning in the post-Soviet space, investigating how autocracies best survival practices.

Over the past year, he has featured in hundreds of media clips, including for France 24, Newsweek, and Euronews and many more. Read more from Stephen via The Conversation.

Geopolitics of War: Prof David Galbreath

The support for Ukraine in the face of Russian aggression has been split between two groups. Material aid and support has largely come from ‘Western’ countries, which include Australia and New Zealand but is dominated by the United States and European countries. This support has largely been in the forms of arms transfers and aid budgets.

At the same time, there has been other support, though less in terms of material aid, by countries that see Russia’s actions in Ukraine as a form of colonialism or a violation of once agreed national autonomy and territorial integrity that has now been reneged by the former coloniser. This latter view of the war in Ukraine has led many states especially in Africa, Asia and Latin America to remain frosty to any attempts to be seen to side on the side of Russia in the war.

Yet, ‘Western’ aid and support is the key to Ukraine being able to continue to fight and has been since the first shots were fired in 2014. NATO, a defence alliance where Ukraine is not a member, has come to be the greatest contributor to the defence of Ukraine. Eastern NATO, namely the Baltic States and Poland, have been strong voices and supporters of Ukraine, unsurprising given their own experience of Russian aggression in the 20th century. Western NATO has given the most aid, with the United States, Canada, the UK and the Netherlands being primary contributors, among others. Nearly all NATO members have given material aid and support to Ukraine, though the Hungarian response has been more muted given the close relationship that president Viktor Orbán has had with Russian president Vladimir Putin over the years.

In addition to NATO members, some traditionally neutral countries have also supported Ukraine either tacitly, as in the case of Ireland, or by changing their state as neutral countries like Finland and Sweden (who have sought NATO membership). Austria and Switzerland are the two neutral countries that some would call complicit in Russia’s war on Ukraine.

Russia is keen to hold out long enough to the point that Western resolve begins to falter. While officially NATO looks solid in its commitment to support the defence of Ukraine, there are alternative views, particularly in but not limited to the United States, that either see that their countries should not be arming a conflict or are sympathetic to Russia in the war. Ukraine is likely to be able to continue to defend itself as long as Western support remains solid. Should that support begin to falter, Ukraine is more likely to need to compromise with an uncertain and untrustworthy adversary.

~

David is Professor of International Security. His expertise spans defence and war studies with a particular focus on how science and technology influences doctrine, concepts and tactics.

Over the past year, his analysis has featured in hundreds of media items, including amongst others for New Scientist, iNews, and across the BBC.