‘When you lose a child it doesn’t matter how they died. When you lose a child, you lose a child,’ Irene MacDonald tells me as she recounts the circumstances surrounding the death of her youngest son, Robin, nearly 19 years ago following a heroin overdose.

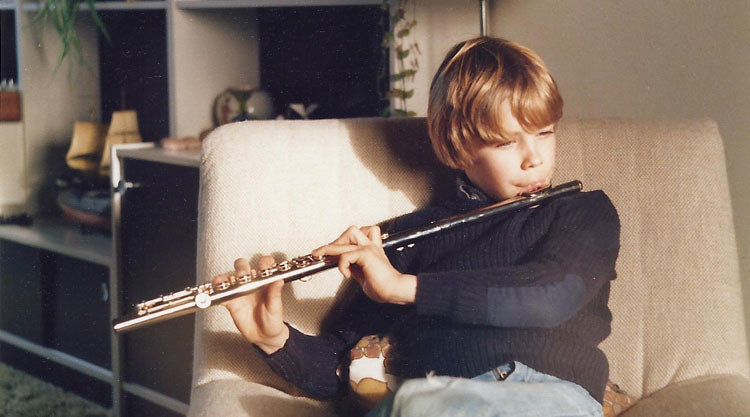

At the time of his death in the late 90s, Robin (Rob, on the right in the picture above) had battled with heroin for some time, but the family were optimistic about his chances of recovery, not to say completely unprepared for the shock news of his death and the events that were to follow.

It was an otherwise ordinary Tuesday evening in November when the MacDonalds, Irene and her husband Ian from Cheltenham, learned of Rob’s death. Home from work, Irene was settling down to watch TV, while Ian was getting ready to meet friends for a night out. Then the phone rang. It was Rob’s partner.

‘She told us she had found him dead in their house when she came in from work. We got into the car and rushed over.

‘I don’t remember much of the journey but when we arrived, there were already loads of people there. Police, paramedics, the coroner’s officer.

‘What I remember most is the police treating Rob’s house as a crime scene. They kept calling him “the body”, told us we couldn’t see him and asked us to “go away”.

‘When Rob was taken away we didn’t know where he had been taken to. It was just horrendous’, recounts Irene.

In the end it took four days before Ian and Irene could see Rob, something the family consider to be ’days of absolutely unnecessary stress.’

Bereavement by alcohol or drugs

The MacDonalds have been part of a large study informing research into bereavement for those affected by drug or alcohol related deaths, led by members of our Centre for Death & Society and collaborators at the University of Stirling.

The findings were used by a working group of practitioners to produce a set of guidelines for how best to interact with people bereaved by alcohol or drugs.

Last week, the three-year ESRC-funded project, which began in September 2012, concluded with the launch of new guidelines. They are for both practitioners and members of the general public.

The 20-page report points to the many challenges faced by people bereaved in this way, including dealing with the stigma associated with such a death, the lack of meaningful support provided through official channels, specific challenges posed by multi-agency working, and the media’s intrusion on grief.

Showing kindness, compassion and humility

All deaths come as a shock, and this can be especially true for deaths by alcohol or drugs. Those left behind may not have known about the person’s substance use, which can lead to conflict between them. Some families may have been coping with the frustration, stress and pain of a person’s substance use for many years; others will feel that they ‘lost’ the person they previously knew many years ago.

Whatever the circumstances, researcher Dr Christine Valentine explains, such bereavements are often united by the fact that the death may be considered taboo and stigmatising which can lead to the bereaved person feeling shame and alienated at the worst time of their life.

‘Bereavements by drugs or alcohol are very often complicated by a belief that a death was premature and could have been prevented, feelings of guilt that family or friends were not able to help, the involvement of the police and sensational or judgemental media coverage,’ says Dr Valentine.

For the MacDonalds, what was always going to be a stressful time could have been made a whole lot easier with a little more compassion, humility and a less stigmatising reaction both from certain professional services, the media and wider society.

‘The only person who showed me any compassion was a paramedic,’ says Irene, recounting the ways in which they assured her and comforted her in a moment of personal crisis.

‘It might sound obvious,’ adds Dr Valentine, ‘but quite clearly there are shortcomings in how individuals in frontline services interact with people bereaved in this way. First impressions can be lasting ones, so showing compassion, understanding and humanity means a lot.’

Language matters

From qualitative research, the authors of the new report reflect on how subtleties in language often compound the stigma associated with a substance-related death, unlike, for instance, a death from cancer or a heart attack.

‘The first thing the police said about Robin was “we didn’t know this guy’,” Irene tells me. ‘Their reaction was, because he was a heroin user, he must be a criminal and they seemed more concerned that there could be an outbreak of deaths [because of the batch of heroin] rather than the fact that our son had died.’

A simple act of offering condolences is just as important here as in any other bereavement, says the research team. To start conversations with ‘I’m very sorry to hear about the death of your son’, would be a good a place to start. Everyone deserves dignity and respect in death.

‘Our research has found that, while poor responses from services can add to people’s distress and grief, a kinder, more compassionate approach can make a real difference,’ adds Dr Valentine.

The language we use in relation to substance use is important, but so too are the ‘trite phrases’ many feel compelled to offer around the time of a bereavement. The guidelines warn against some common statements, not least ‘I know how you feel’ (when many of us clearly do not, and even if we do, our situation can be very different) and why it’s important to treat everyone’s grief as unique to them.

‘I know people mean well, but when someone said to me “move on”, I just thought “move on where?” Someone even said to me “at least you’ve got another son”,’ Irene says.

On the front line

There is no denying that frontline services are stretched. From first-on-the-scene emergency services through to counsellors and support groups, services face very real challenges associated with deaths from alcohol or drugs.

The authors of the new report highlight the complexities of multi-agency working but point out that more can be done to improve the flow of information and how small changes in service support could make a huge difference for individuals involved.

Christine Hurst is a Senior Coroner’s Officer and runs a team responsible for investigating all sudden deaths in Cheshire. With over 200,000 sudden deaths a year (47 per of all deaths reported), Chris and her team have substantial contact with bereaved. Chris was on the working group that produced the Guidelines.

‘I appreciate that families who are bereaved through alcohol or drug use may well feel that there is a stigma attached to that. It is therefore really important that in the coroner’s service we are non-judgemental and that we treat everyone with respect and dignity,’ she says.

‘We have to hone our communication skills to pick-up on signals from the family and whether we can start talking about sensitive issues or whether we need to delay that.’

In cases where someone is bereaved through alcohol or drugs, it’s normally the coroner’s office that acts as a support through the process and a conduit through the large web of individuals and agencies.

The new research reveals an incredibly complicated picture of all organisations and individuals bereaved people may speak to.

‘One of the first things that could significantly help people facing bereavements by alcohol or drugs is for the services they come into contact with to familiarise themselves with what other support is out there. Too often, information is in scant supply and it’s left to the bereaved person to guide themselves through the system,’ argues Dr Valentine.

Learning to live with bereavement

This is the situation that Ian and Irene faced around the time of Rob’s death. Their dedicated Family Liaison Officer saw them only once before going off on sick leave and the couple felt that they were left completely on their own.

‘I went to the Citizens’ Advice Bureau, then I went to the Library,’ Irene recalls. ‘I had two leaflets thrust into my hands with numbers that were out of date.’

‘So we set up our own service,’ adds Ian.

Four years after Rob’s death, the MacDonalds set up Carer & Parent Support Gloucestershire (CPSG), a small voluntary organisation offering support via telephone, Skype, email and face-to-face to family members whose lives have been touched by drug use.

The regular interaction with people who have faced similar challenges with family members has helped Ian and Irene with their own grieving process.

‘As we reflected on things through our period of grieving we suddenly decided that, if anything positive was to emerge from Robin's death, there might be something we could do to help other people in a similar situation.’

Making an impact

Many of us feel uncomfortable or unsure about how to respond to people bereaved by alcohol or drugs deaths. How we talk about these deaths and the support available is perhaps symptomatic of the fact that, for too long, this kind of bereavement has remained hidden and neglected by research, policy and practice. These new guidelines are an opportunity to change that.

‘It never does anyone any harm – no matter how long you’ve been in a profession – to actually stop and reflect. I think these guidelines make you stop and reflect on how you communicate, “have I done my best?”, “could I do better?”,’ Christine Hurst from the Coroner’s Office says.

‘Our hope is that these guidelines – developed by practitioners, for practitioners will provide a much needed blueprint for how services can better respond to bereaved people. Subtle and often simple changes can make a big difference in someone’s grieving process. It is our hope that others don’t have to go through the same situation as the MacDonalds,’ Dr Valentine says.

In the process of writing this feature I have a chance conversation with Ben, someone still raw with the emotion of a very recent drugs-related bereavement. Just over a week ago, he tells me, he arrived home to find his housemate, aged in his late 20s, dead in his room following a drugs overdose.

Visibly still shaken by the whole affair, yet seemingly still wanting to talk about it, he recounts the different responses he and his friends received from the emergency services and praises an ‘excellent paramedic’ who attended the scene. He also tells me how he will soon take up an offer of counselling in an effort to start to try to make sense of such a tragic and shocking event.

I check myself and my language, mindful of the impact I could have on his grief. I don’t work in frontline services, but I am thankful to have read these recommendations. None of us know what lies ahead and when these might come in useful.

Dedication

The Guidelines are dedicated to Joan Hollywood (1941-2015). Joan’s son died in 2008 as a result of drug and alcohol use. Unable to find support for grieving a death related to substance use, Joan and her husband, Paul, founded Bereavement Through Addiction (BTA), in Bristol.

BTA provides a helpline, support groups and an annual memorial service for those bereaved in this way, as well as providing training to organisations in the field.

A tireless campaigner for people bereaved through substance use, Joan was a key inspiration for the research on which these guidelines are based, a member of both the research team for the project as a whole and of the working group that produced the guidelines.

The guidelines are a lasting memorial to the achievements of Joan, who died shortly before they were published.